Agroforestry Plantation of Culturally Significant Plants

Introduction

A reoccurring revelation breaks on me anew nearly every time I spend an appreciable amount of time in the forest; one that renders me mute and pondering in stunned silence: the forest provides everything we need to sustain our lives. Food, medicine, shelter, clothing, tools, and right livelihood. In particular I am struck by the myriad healing qualities of native plants; right there in the woods are plants that will help stop bleeding and close wounds, alleviate pain, reduce fever, boost the immune system, fight cancer, and so much more. It’s a little hard to not flirt with the notion of a Grand Design, but I recognize the co-evolutionary capacity of organisms that share the same environment. Instead I find myself asking “who started the myth that we were kicked out of the Garden of Eden? We’re living in it!”

The study of human uses of plants is referred to as ethnobotany. There is a vast repository of knowledge of native plants in the cultures of the first peoples who have inhabited this land for millenia. Early settlers acquired many skills and uses of the forest from native Americans, and also brought with them their own cultural understandings of plants. Today there are innumerable books and websites dedicated to documenting and disseminating information on ethnobotany. My curiosity of this subject took hold when I was quite young. My family travelled extensively throughout the state I grew up in, Minnesota, which hosts many Native American communities. We visited the cultural centers of these communities and I was always fascinated by the many ways the people utilized the products of their environment. My parents owned forestland and also took a multiple-use approach to it. They processed maple syrup from the sugar maples, cut firewood, leased hunting rights, collected spring water, and recreated.

Over the years I’ve familiarized myself with the panoply of ethnobotanically significant plants in my forest. My family harvests several of them on a regular basis, including: nettles, Douglas-fir tips, mushrooms, and, of course, lots and lots of berries. There is enough structural diversity in my forest (edges, gaps, areas of thin canopy, etc.) that I feel it’s capable of producing far more than we could possibly harvest or use without any need for additional management. Therefore, I haven’t adjusted any of my management practices solely for the benefit of any specific plant, other than thinning to maintain good timber production. All the same, I’ve long thought it would be fun and interesting to intentionally cultivate certain ethnobotanical plants, either through manipulating the structure and composition of my forest, or by planting an agroforestry plantation dedicated to the production of culturally significant plants.

It was to my delight I learned that the federally funded Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) provided funding to rural landowners specifically for the purposes of establishing “Cultural Plantings”. The program is funded by the Farm Bill and managed by the Natural Resources Conservation Service, an agency within the USDA. The USDA defines Cultural Plantings as:

… trees and shrubs that are of cultural significance, such as those species utilized by Tribes in traditional practices, medicinal plants, species used in basket-making, etc.

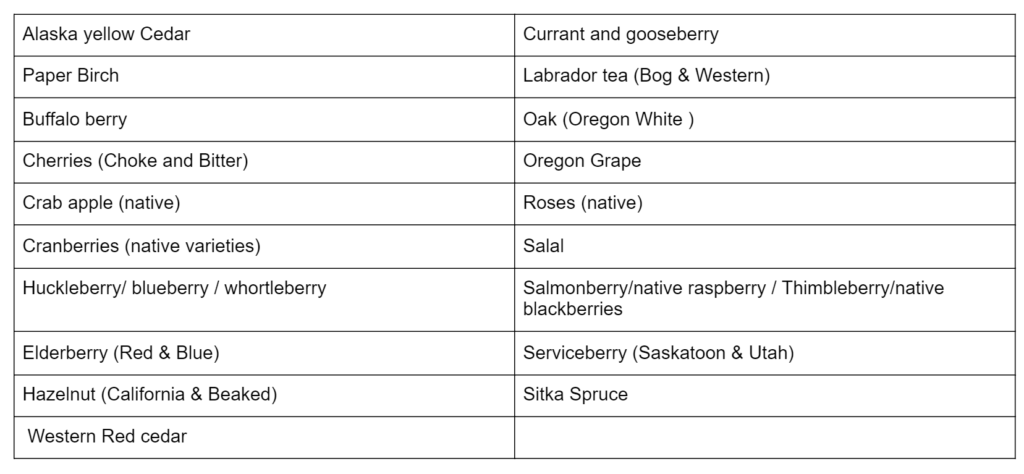

The guidelines for this conservation practice also include the following list of plants known to have cultural significance to native Americans in Washington State, although other plants that do not appear on this list also qualify:

With the dual incentives of financial assistance and a contractual mandate I applied for and received CSP funding in 2019 to establish both a one-acre wildlife forage hedgerow and a one-acre cultural planting. CSP provided $1,400/acre for each of these practices to be spent on site preparation, purchasing planting stock, planting, and any browse protection as necessary. CSP also provided additional funding to support the ongoing stewardship activities I’m implementing across the remainder of my forest, and some of this funding will be used to maintain both plantations once they’re established. The wildlife forage hedgerow was planted in the winter of 2019/2020 and I’ve written about it elsewhere.

Planting Plan

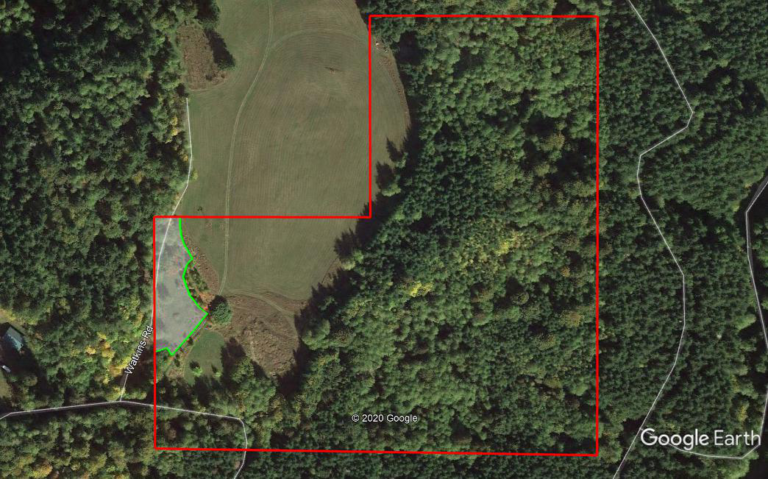

The one-acre site I selected for this project occurs along my western property line. The site is a fallow field that I mow annually solely to prevent invasive species from colonizing it. The vegetation is chiefly composed of reed canary grass, Himalayan blackberry, thistle, and a variety of other native and non-native groundcovers and grasses. The northern portion of the unit is composed of a variety of hardwoods, namely alder, Oregon ash, and birch, which were planted 15+ years ago. A couple small patches of naturally seeded red alder occur within the site, and a small plantation of basketry willows occurs along the southern edge of the unit. Soils can be quite wet in the winter, and dry out quickly in the summer.

When I first began researching plants to include in my ethnobotanical agroforestry plantation, it quickly struck me that I would be hard pressed to identify a native plant that did not have some value to humans. Would I then just be planting a native forest not dissimilar to the one already growing on my land? I wanted to have some kind of creative twist to this project, so here’s what I settled on.

The plantation is designed to mimic the structure of the edge of a forest, utilizing a combination of tall hardwoods and conifers, low trees, shrubs, and groundcovers in a graduated fashion that minimizes competition between the species. Shade tolerant trees and shrubs will be planted beneath existing hardwoods on the site, sun-loving hardwoods and conifers will be planted along the western property line, and sun-loving shrubs and groundcovers will be planted in the most open portion of the field. Further, each species will be planted in groupings of the same species to aid in both management and future harvest. The following criteria were used to select the plant species:

- ability to propagate from the site,

- availability of naturally regenerating seedlings,

- increase abundance of an existing species,

- provide specific species more optimal growing conditions (e.g. full light),

- opportunity to trial new species

- species adapted to wet winter soils and dry summer soils

The one-acre site will be planted with 450 trees and shrubs. If all plantings were evenly distributed across the site, they would be spaced on a 10’x10’ grid. However, given that approximately ⅓ of the site is already occupied by a relatively dense mix of hardwoods, the planting strategy will be variable, with some shrubs planted in groupings at a higher density (e.g. shade-tolerant shrubs beneath existing hardwoods) and the hardwood and conifer trees planted on a 10’x10’ spacing.

Ethnobotany Species

Open inventory of ethnobotany species I planted.

Site Preparation & Planting

I’ve planted trees and shrubs into grassy fields often enough to know that it is risky business. There are few more punishing sites for newly planted seedlings than pasture or hayfields. Grass regrows quickly, can smoother short seedlings, competes intensely for moisture in the same soil horizon as the seedling, harbors mice and voles that can girdle seedlings, and, if those aren’t dissuasive enough qualities, it wages an underground chemical warfare on other plants by exuding a growth inhibiting hormone referred to as an allelopathic chemical. Soils that have produced grasses for decades also have a remarkably different soil biota than woodland soils, and tend to be more bacterially active than mycological. Trees and shrubs adapted to woodland soils have a hard time getting established in this foreign environment. Couple these idiosyncrasies with a heavy clay soil that dries quickly in early summer before turning to cement and you might begin wondering why anyone would attempt to plant into such conditions. I am a hard-headed Norwegian though, and both culturally and existentially predisposed to taking the path of most resistance.

Given the prevalence of reed canary grass, a particularly tenacious and pernicious invasive grass, and Himalayan blackberry on the site, I finally turned to herbicides for the first time in my life and hired a licensed applicator. The herbicide contractor used an all-terrain quad with a tank and boom mounted on the back with which he sprayed the entire acre in less than an hour. We applied Vastlan, a triclopyr-based herbicide that specifically targets broad-leafed plants, in early October, prior to the first frost, and on a sunny day without wind. Within approximately one month nearly the entire field turned brown, with just a few exceptions where the applicator didn’t quite overlap his passes.

From this point, the following prescriptions will be used for planting each seedling:

- Plantings will be arranged in rows 10’ apart to facilitate mowing when grasses and other vegetation recolonize the site

- Hardwood and conifer trees will be planted on 10’ centers. Tall shrubs will be planted on 6’ – 8’ centers. Low shrubs will be planted on 4’ centers.

- All shrubs will be planted in groupings of the same species.

- A planting site at least 3’ in diameter will be scarified to bare soil using a brush cutter and string line attachment

- The sod layer will be cut away from the planting hole and discarded

- Planting holes will be dug approximately twice the volume of the seedling’s bare root system

- A 3” – 5” thick mulch of wood chips will be placed within a 1’-2’ radius around each seedling

- Protective tree tubes will be placed over the seedlings to prevent girdling

The woodchip mulch serves the dual purpose of retaining soil moisture later into the season and facilitating the reintroduction of mycelium into the soil.

Care & Maintenance

When planting is complete, the following maintenance strategies will be applied:

- Competing vegetation will be cut back from around each seedling until it reaches a free-to-grow condition. This may include mowing between planted rows, brush cutting around seedlings, and/or manual control of weeds by hand pulling or machete

- A browse-repellant may be used to deter deer and elk

- Tree tubes will be straightened as necessary and removed once a tree reaches 5’ or a shrub reaches its height potential.

Leave a Reply