Are We Old Growth Yet? NNRG Turns 30!

Since its founding in 1992, NNRG has been led and staffed by a small, rotating band of idealists and innovators. 30 years later, though the team remains small, the impact of our work has spread as swiftly as a field of salmonberry that’s found a gap in the canopy.

When NNRG sprouted 30 years ago in Port Townsend, it went by another name: the Olympic Peninsula Foundation, or OPF. In the early part of the 1990s, OPF was focused on improving salmon habitat and stream restoration in the Olympic Peninsula, and providing jobs to forest workers who had been left unemployed when the Northwest Forest Plan was adopted, setting much of the US Forest Service’s old-growth forests off-limits to logging.

But since salmon and forests are inextricably linked, OPF eventually turned its eye toward forest management practices that sustain and improve ecological health. Denise Pranger and Larry Nussbaum, both on staff at the time, came to the board with a proposal: shifting the organization’s focus to Forest Stewardship Council (FSC®) certification. The board said sure—find us replacement board members, and we will hand you the organization. Larry secured a grant to launch the first FSC® training program in Washington, and Denise Pranger was hired as Executive Director. “It was hilarious,” says Denise. “We had funding, staffing, a strong mission…but no board of directors.”

NNRG’s Early Seral Stage

Undaunted by the sudden absence of a board, Denise and Larry, set about recruiting new board members. In 1998 they had their first board retreat, and within a few hours of that the organization had a new name: Northwest Natural Resource Group.

“People were hungry for certification, hungry for the possibility of ecological forestry getting recognition,” says Denise. “It was a huge success…we had people come in to take our trainings from all over the country.”

At the time, most certification programs for everyday consumer products were just gaining steam. “We had jokes about FSC® being a flash in the pan, and there were of course some people who were like, What are you doing?, but when the label started showing up on the back of Victoria’s Secret catalogs they started taking it seriously.”

For several years, NNRG expanded its certification program. “FSC® was the bedrock of what we did,” says Denise. “It set the standard for the kind of forestry we were interested in.” Private landowners, land trusts, and public agencies were eager to get the public recognition of good forest stewardship that came with FSC® certification. At the same time the organization was securing grants to do research measuring the tangible benefits of FSC® certification for ecosystem services like water quality and soil health.

NNRG launched its own group FSC®-certification in the early 2000s, which made FSC® certification suddenly more available—and more affordable—for smaller forested parcels. But, says Ian Hanna, who was hired in 2006, “it also became really clear that we were not going to build a business off of certification.” The smaller a property was, the higher the cost per acre to certify it. NNRG couldn’t sustain its work on grant funding and FSC® certification alone.

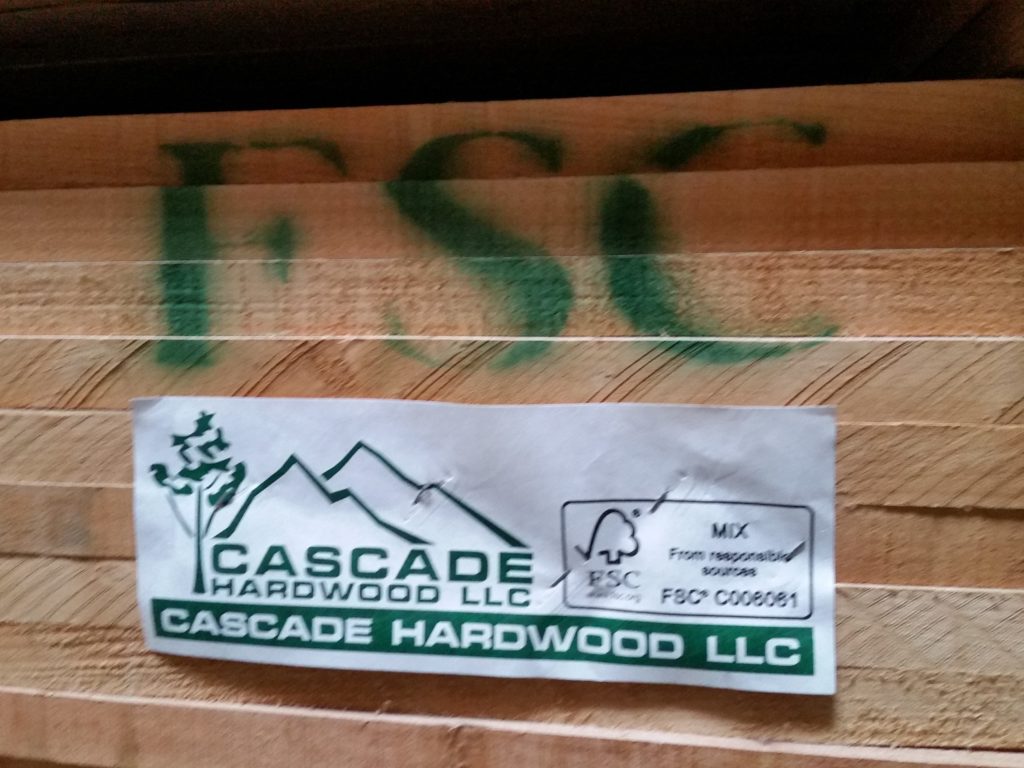

Kirk Hanson, who currently serves as NNRG’s Director of Forestry, was hired around the same time. “For the first five years or so that I was working with NNRG, we put a heavy focus on FSC® certification and helping a broad suite of forest owners get certified, as well as everything we could do to build FSC® markets for logs and lumber products.”

“That was a really hard task,” says Kirk. “So we started shifting our focus to just…better forest management. Articulating what ecologically-based forestry really is, and realizing that there was not a lot of research out there—or at least research that was then leading to implementation.”

“Those were really exciting days for NNRG, because we felt like we’d finally found the perfect niche. We decided we would do research and development [on better forest management] and provide consulting services and on-the-ground forest management services for small woodland owners.”

The NNRG staff was still very small back then. “It was Denise Pranger, who was an extraordinary visionary and just a force of nature,” says Kirk. “Ian Hanna, who brought with him expertise in Forest Stewardship Council certification and small-scale wood manufacturing; and me, a small woodland owner who’d worked for years in the Small Forest Landowner Office of Washington DNR.”

Back then, says Ian, NNRG’s special sauce was its ability to aggregate the needs of individual small forest landowners in a way that led to individual benefits they wouldn’t otherwise have seen. The group FSC® certification model wasn’t the only example of this; NNRG worked hard to convince landowners with neighboring properties to conduct forest management activities like thinnings at the same time so as to cut harvest costs and gain access to higher-paying log buyers.

No Longer Saplings

In the early 2000s, while its FSC® certification program was transforming and broadening to include other forest management services, NNRG began making forays into the forest carbon market for small landowners. The concept of paying forest owners for sequestering carbon in their forests was very, very new – at least in Washington. “We were definitely the tip of the spear on that,” says Ian. At the time, the staff and board felt carbon markets could be groundbreaking in making ecological forestry more economically feasible for small forest landowners.

In collaboration with consultants and experts in carbon accounting, NNRG developed a field methodology for measuring carbon stocks in forest stands—the first of its kind in Washington—then launched Northwest Neutral soon after. The new program certified forest carbon offsets and sold them into the voluntary carbon market.

It was a gamble that didn’t pay off. Despite a great deal of worldwide fanfare and optimism, voluntary carbon markets never became the climate solution people had hoped for. In time, most voluntary carbon offset projects would come to start with a buyer already identified, to ensure that there would be demand for the documented offsets. Instead, Northwest Neutral started by finding the landowners willing to commit to a carbon project, and then hawking the offsets after the fact—a model that proved financially infeasible. The ‘08 economic downturn further deflated demand for carbon offsets, and Northwest Neutral’s carbon projects foundered. “That just took all the…I was going to say ‘all the oxygen out of the carbon market,’ but that doesn’t make much sense,” laughs Ian Hanna.

Today, Kirk looks back on the carbon project as one of NNRG’s critical periods of growth. “That was part of our innovation. Not everything’s going to be successful, but [the carbon project] revealed to us the extraordinary potential of Northwest forests to sequester carbon and the breadth of silvicultural practices that we could implement to improve carbon sequestration. I think our era of working with carbon was fundamental to informing the forestry that we’re doing today.”

On the Way to Old Growth

Denise Pranger left NNRG in 2011, having shepherded the organization as Executive Director for more than a decade, from being seed of an idea to a fully-fledged nonprofit with a secure foothold in the forest management and certification sector. She remembers NNRG’s early days proudly. “In the early years, forest certification as a concept was the most interesting, crazy, fun exciting thing I’d ever heard of in the ecological movement. It was an evolving, best available science, democratic process that could be cumbersome at times but was so rational and such an interesting way to engage so many people around the world in forestry and therefore ecology.”

She credits NNRG’s board of directors for helping transform NNRG after the carbon program stalled and Dan Stonington took over as NNRG’s Executive Director. “Watching NNRG remake itself was incredible. The board of directors who worked with Dan to stabilize NNRG when carbon couldn’t happen—they were incredible. They stuck it out and believed in it. And Dan was the perfect person to take over when I was tapped out.”

Under Dan’s leadership, NNRG moved from Port Townsend to Seattle. “Dan brought this incredible business acumen with him and began managing NNRG with more of a business mindset,” recalls Kirk. “We got a lot better at doing forest management planning, and we started providing timber harvest services too. So all of this was bringing revenue into the organization, and that really stabilized us.”

“When I joined NNRG I was so inspired by the people that the organization was working with and the mission to pursue market-based conservation tools,” says Dan. “It felt like there was a lot of room to try out new ideas and show successes on the ground that could lead the broader community of government partners, of NGO partners, of small forest landowners, toward applying better forest management solutions on a broader scale.”

In its last decade, NNRG has grown wider rings, so to speak. Under the leadership of board President and FSC®-certified forest owner Christine Johnson, NNRG got serious about strategic planning: our Strategic Plan—the fourth in a series of three-year plans—lays out specific, measurable targets for the coming years and the steps we will take to achieve them.

While remaining a small and local organization by design, NNRG has been able to rapidly adapt and respond to changes and opportunities in the forestry sector, to ensure the field remains accessible to small landowners while it evolves. We now have a staff of ten, including six foresters, and our board of directors includes leaders from sectors that interact with and influence forest practices in the Northwest, including sustainable wood products, architecture, higher education, and corporate sustainability.

Since 2012, our FSC® program has nearly doubled in size to nearly 200,000 acres that are certified to the highest forest management standards in the world. Our FSC® group certificate is the largest in the Pacific Northwest, representing about a third of all FSC forests in Washington and Oregon.

NNRG continues to spread the word about ecological forestry around the region, educating forest owners, managers, and practitioners about the benefits of balanced forest management. In the last decade alone we’ve put on workshops and tours that have been attended by over 1,200 people, and conducted more than 500 site visits to help landowners set a course for their forests. We’ve written 145 forest management plans covering 73,644 acres of forestland. And we’ve managed over 70 harvests in the past decade that improve forest health and bring in sustained revenue for landowners.

In partnership with universities, landowners, and community forests, we’ve launched projects that explore forest management strategies that build climate resilience, and spearheaded research on the economic outcomes of thinning versus alternative forest management strategies.

“I left NNRG in 2017,” said Dan Stonington during a recent interview, “and in the last five years, I think the organization has really sharpened the expertise that it’s providing and the data and success stories that it’s providing for what it looks like to make ecological forestry happen on the ground. I think [NNRG is] going to play an essential role in the future. We’re going to have to respond to the pressures climate change poses, to population growth in this region, to more demands on our ecosystems and the services that we’re trying to get from them. And I think NNRG is positioned really well to be that sort of innovator, that experimenter with new approaches, to be able to show what works on the ground and put theory into practice.”

The Next 100

This past May, fifteen of the NNRG board and staff gathered around a table in a small room in Potlatch, Washington. It was the first time many of us had seen each other in person for at least two years, and the conversation ebbed and flowed between strategic planning and side-splitting stories about working in the woods. “When you get that many committed, inspired forest enthusiasts together, the sky’s the limit. It just launches you right up into the overstory,” says NNRG Executive Director Seth Zuckerman.

“I’m excited about the next 30 years for NNRG,” says board member Ben Hayes, who is also one of the stewards of Hyla Woods in Oregon, “The world is going to change so much. We need forestry organizations that are able to lead through that change and help forge models for forest management that work not just for the next 30 years, but for the next hundred.”

Thanks to Denise Pranger, Ian Hanna, and Dan Stonington for their help in writing this article—and their years of bold and creative leadership. Thanks also to all of the current and past NNRG staff and board members who’ve been on the NNRG team over the years.

Leave a Reply