Beavers as Partners in Riparian Restoration

Free subcontracting? We’ll take it!

By the time Beth and Mark Biser bought Still Waters Farm in 1990, the 48-acre property in Mason County, Washington was a shell of its former self. Its 20 acres of wetlands had been mined and drained, and the forest was quiet.

With a vision of a healthy wetland and forest ecosystem in mind, the Bisers applied for and won a small grant from the US Fish & Wildlife Service to start restoring the land in 1994. The project was unpretentiously titled Small Ponds for Wildlife.

They used an excavator to dig a series of small ponds connected by channels of water, and built peat islands here and there. After mowing down a monoculture of Douglas spirea, a more diverse community of sedges, rushes, and grasses moved in naturally. Ash and cedar were planted for additional diversity, and would make good beaver food in the future. (A previous article about the forest’s restoration can be found on NNRG’s blog, here.)

And as they worked on restoring the hydrology of the forest, something amazing happened: beavers moved in, and eagerly set to work restoring the hydrology on their own.

“As we began working to plug the ditch, the beavers came in and plugged it for us,” says Mark. “They were working in an artificially deepend drainage channel that was ten feet deep and twenty feet wide, and over the course of a season they moved at least 20 yards of rock and big woody material into the breach. They raised the level above even what we had planned for.” Eager beavers indeed!

Beaver dams are temporary. Their rodent residents do maintenance, but high flows can knock them down – which is what happened in 1998, when a hundred-year flood took out the dam the beavers had built in the man-made ditch. Water was once again draining out of the wetland.

Mark Biser had an idea: he had heard that the sound of flowing water stimulates the dam-building instinct in beavers, so he drove stakes into the center of the now water-filled ditch to encourage them to “repair” their now blown-out dam. Sure enough, those dam rodents got to work!

Previous

Next

The Bisers wanted a more stable system, so they continued the restoration work and permanently stabilized the hydrology with a control structure at the outlet of the ditch. But the beavers were there to stay, and today Still Waters Farm is home to two families. Each is usually comprised of two adults, two or three teenagers, and two or three kits.

“We don’t see them often,” says Mark. “We’ll see them on the shoulders of the day, early in the morning. We’ll hear their tail-slap alarm calls.”

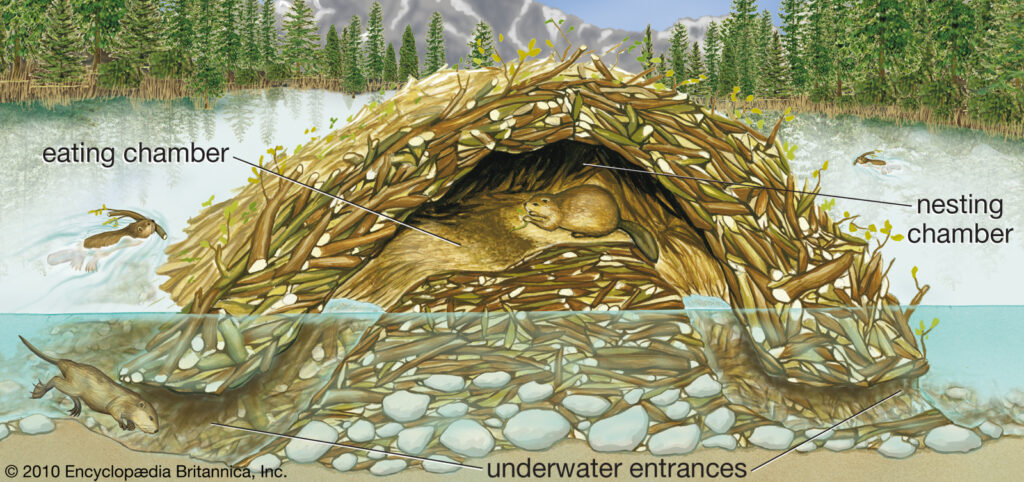

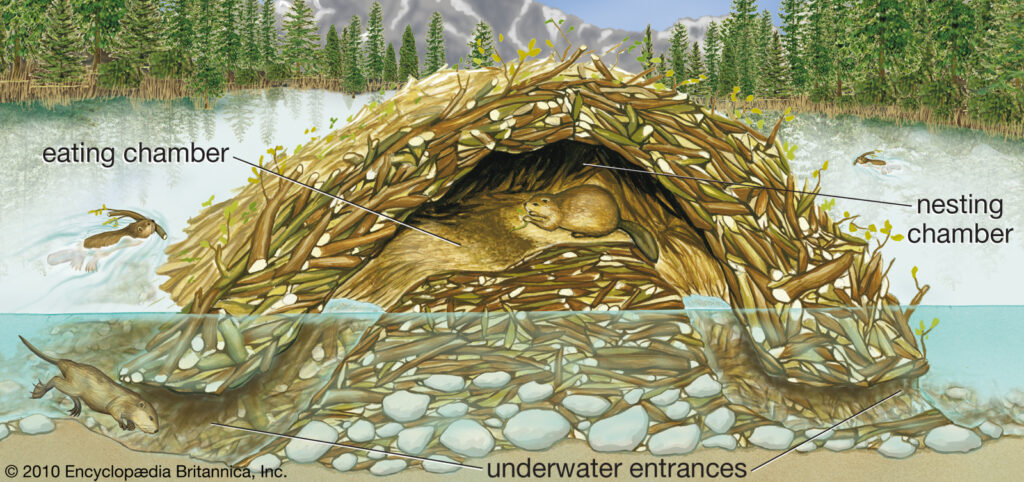

One family occupies a den that they excavated out of soft soils on the margins of the Biser’s pond. The other, a 10-foot high lodge built in the middle of the pond. Beaver lodges often contain multiple underwater entrances and interior chambers engineered for different purposes.

When beavers munch…

The Bisers have a good relationship with the resident rodents, although, Mark notes, “It seems like the more I like trees, the more they like to eat them.”

Beavers are vegetarians. They eat the bark, stems, buds, and twigs of trees, and some types of aquatic vegetation. At Still Waters Farm they munch on willow, Sitka alder, hazel, shore pine, and lodgepole pine. But their favorite food when they can get it is western redcedar up to four inches in diameter. “Which is irritating because I planted a lot of cedar in the riparian zone.”

Like many forest owners who coexist with beavers, the Bisers have made an effort to safeguard high-value trees, usually by wrapping chicken wire or fence wire around them. And that worked well – for a while. But, says Mark, “they’ve become more aggressive, or they’ve learned. It used to be if there was any wire on a tree at all, that seemed to dissuade them. But now they’ll go in and push down the wire or eat above it to get at the trees.”

Beavers and their insatiable stomach for trees! Living with beavers usually does mean accepting that they will take down or girdle some trees within a radius of their lodge (around 50 yards is common). But the distance they travel for food and building materials depends on the availability and age of preferred trees near their lodge. Land managers and forest owners can take different approaches to living with beavers:

- Choose and place plants carefully: When replanting in riparian and beaver-prone areas, consider species that are already adapted to beavers – that can resprout from stumps once their roots are well-established – like aspen, cottonwood, willow, spirea (hardhack), and red-twig dogwood.

- Install barriers: High-value or special trees can be wrapped with various forms of galvanized, welded wire. Stakes can be used to reinforce the wire fencing or cage, as beavers do lean on wire to get to trees and can bend or crush weaker fencing. Keep a 2-foot space between the wrapping and the tree stem, and the wrapping should be at least 3-4 feet high. These fences/cages must be widened as the trees grow.

- Paint trees: Painting trees with various stinky or gritty substances that deter beavers can work, but often requires multiple applications per year, so is a time-consuming option that yields mixed results. A commonly-mentioned combination is one of oil or latex paint and sand. According to the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife, “Taste and odor repellents are most effective when applied at the first sign of damage, when other food is available, and during the dry season.” But use caution: painting immature trees or young plants with these mixtures may harm or even kill them.

Becoming a Beaver Believer

In the end, beavers are a natural part of many Pacific Northwest riparian ecosystems, and learning to live with them — and appreciate their engineering prowess! — is important.

As Washington DNR Stewardship Wildlife Biologist Ken Bevis writes in his article, I’m a Beaver Believer:

Tolerance and enjoyment: If you are fortunate enough to have beaver on your forest land, be glad! Yes, they will chew some trees and flood a few others (often alder it seems), but will raise your water tables, (especially important in the hot, dry summer), provide habitat for a myriad of species including many birds (think wood ducks and flycatchers) and amphibians (Rough skinned newts and Western toads), and create a wildlife oasis in our forest lands.

And Mark Biser seems to agree, saying, “They’ve added a lot of complexity to the wetland, and stability. We’re fortunate in that other than murdering some of my favorite trees, they haven’t caused any damage. And they raise the water level, which is helpful for the fish and the other species.”

Beavers and salmon have coexisted for millennia, so contrary to what you might think, beaver dams do not block fish passage, and they don’t raise water temperatures downstream. Salmon spawning coincides with heavier fall and winter rains, so salmon are able to pass over dams when the water level rises. They can also pass through small holes in beaver dams. The ponds created by beaver dams make for fabulous, well-protected habitat for juvenile salmon.

But wait, there’s more! In the Pacific Northwest, we have a wide range between winter wet and summer dry conditions. The range is only expected to grow with climate change. Luckily for those who live with beavers, their dams provide water storage and act as a hydrological buffer for the land. “They keep systems from being so flashy,” says Mark. “They’ll hold excessive rainfall and slowly weep it out.”

Altogether, Mark is pleased with the presence of his furry rodent forest co-residents. “They do a lot of the maintenance work. And at relatively low cost, in terms of what they eat. They’ve been a lot of fun.”

Resources on co-habitating with beavers

Frequently Asked Questions about Beavers – Washington Department of Natural Resources

Living with Wildlife: American Beaver – Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife

Species Factsheet: Beaver – Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife

Beaver, Muskrat and Nutria on Small Woodlands – Woodland Fish & Wildlife Series

Identifying and Managing Mountain Beaver Damage to Forest Resources – WSU Extension Forestry

Beavers Northwest – An awesome group that advocates for the many benefits beavers provide through research, outreach and landowner assistance.

Free subcontracting? We’ll take it!

By the time Beth and Mark Biser bought Still Waters Farm in 1990, the 48-acre property in Mason County, Washington was a shell of its former self. Its 20 acres of wetlands had been mined and drained, and the forest was quiet.

With a vision of a healthy wetland and forest ecosystem in mind, the Bisers applied for and won a small grant from the US Fish & Wildlife Service to start restoring the land in 1994. The project was unpretentiously titled Small Ponds for Wildlife.

They used an excavator to dig a series of small ponds connected by channels of water, and built peat islands here and there. After mowing down a monoculture of Douglas spirea, a more diverse community of sedges, rushes, and grasses moved in naturally. Ash and cedar were planted for additional diversity, and would make good beaver food in the future. (A previous article about the forest’s restoration can be found on NNRG’s blog, here.)

And as they worked on restoring the hydrology of the forest, something amazing happened: beavers moved in, and eagerly set to work restoring the hydrology on their own.

“As we began working to plug the ditch, the beavers came in and plugged it for us,” says Mark. “They were working in an artificially deepend drainage channel that was ten feet deep and twenty feet wide, and over the course of a season they moved at least 20 yards of rock and big woody material into the breach. They raised the level above even what we had planned for.” Eager beavers indeed!

Beaver dams are temporary. Their rodent residents do maintenance, but high flows can knock them down – which is what happened in 1998, when a hundred-year flood took out the dam the beavers had built in the man-made ditch. Water was once again draining out of the wetland.

Mark Biser had an idea: he had heard that the sound of flowing water stimulates the dam-building instinct in beavers, so he drove stakes into the center of the now water-filled ditch to encourage them to “repair” their now blown-out dam. Sure enough, those dam rodents got to work!

Previous

Next

The Bisers wanted a more stable system, so they continued the restoration work and permanently stabilized the hydrology with a control structure at the outlet of the ditch. But the beavers were there to stay, and today Still Waters Farm is home to two families. Each is usually comprised of two adults, two or three teenagers, and two or three kits.

“We don’t see them often,” says Mark. “We’ll see them on the shoulders of the day, early in the morning. We’ll hear their tail-slap alarm calls.”

One family occupies a den that they excavated out of soft soils on the margins of the Biser’s pond. The other, a 10-foot high lodge built in the middle of the pond. Beaver lodges often contain multiple underwater entrances and interior chambers engineered for different purposes.

When beavers munch…

The Bisers have a good relationship with the resident rodents, although, Mark notes, “It seems like the more I like trees, the more they like to eat them.”

Beavers are vegetarians. They eat the bark, stems, buds, and twigs of trees, and some types of aquatic vegetation. At Still Waters Farm they munch on willow, Sitka alder, hazel, shore pine, and lodgepole pine. But their favorite food when they can get it is western redcedar up to four inches in diameter. “Which is irritating because I planted a lot of cedar in the riparian zone.”

Like many forest owners who coexist with beavers, the Bisers have made an effort to safeguard high-value trees, usually by wrapping chicken wire or fence wire around them. And that worked well – for a while. But, says Mark, “they’ve become more aggressive, or they’ve learned. It used to be if there was any wire on a tree at all, that seemed to dissuade them. But now they’ll go in and push down the wire or eat above it to get at the trees.”

Beavers and their insatiable stomach for trees! Living with beavers usually does mean accepting that they will take down or girdle some trees within a radius of their lodge (around 50 yards is common). But the distance they travel for food and building materials depends on the availability and age of preferred trees near their lodge. Land managers and forest owners can take different approaches to living with beavers:

- Choose and place plants carefully: When replanting in riparian and beaver-prone areas, consider species that are already adapted to beavers – that can resprout from stumps once their roots are well-established – like aspen, cottonwood, willow, spirea (hardhack), and red-twig dogwood.

- Install barriers: High-value or special trees can be wrapped with various forms of galvanized, welded wire. Stakes can be used to reinforce the wire fencing or cage, as beavers do lean on wire to get to trees and can bend or crush weaker fencing. Keep a 2-foot space between the wrapping and the tree stem, and the wrapping should be at least 3-4 feet high. These fences/cages must be widened as the trees grow.

- Paint trees: Painting trees with various stinky or gritty substances that deter beavers can work, but often requires multiple applications per year, so is a time-consuming option that yields mixed results. A commonly-mentioned combination is one of oil or latex paint and sand. According to the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife, “Taste and odor repellents are most effective when applied at the first sign of damage, when other food is available, and during the dry season.” But use caution: painting immature trees or young plants with these mixtures may harm or even kill them.

Becoming a Beaver Believer

In the end, beavers are a natural part of many Pacific Northwest riparian ecosystems, and learning to live with them — and appreciate their engineering prowess! — is important.

As Washington DNR Stewardship Wildlife Biologist Ken Bevis writes in his article, I’m a Beaver Believer:

Tolerance and enjoyment: If you are fortunate enough to have beaver on your forest land, be glad! Yes, they will chew some trees and flood a few others (often alder it seems), but will raise your water tables, (especially important in the hot, dry summer), provide habitat for a myriad of species including many birds (think wood ducks and flycatchers) and amphibians (Rough skinned newts and Western toads), and create a wildlife oasis in our forest lands.

And Mark Biser seems to agree, saying, “They’ve added a lot of complexity to the wetland, and stability. We’re fortunate in that other than murdering some of my favorite trees, they haven’t caused any damage. And they raise the water level, which is helpful for the fish and the other species.”

Beavers and salmon have coexisted for millennia, so contrary to what you might think, beaver dams do not block fish passage, and they don’t raise water temperatures downstream. Salmon spawning coincides with heavier fall and winter rains, so salmon are able to pass over dams when the water level rises. They can also pass through small holes in beaver dams. The ponds created by beaver dams make for fabulous, well-protected habitat for juvenile salmon.

But wait, there’s more! In the Pacific Northwest, we have a wide range between winter wet and summer dry conditions. The range is only expected to grow with climate change. Luckily for those who live with beavers, their dams provide water storage and act as a hydrological buffer for the land. “They keep systems from being so flashy,” says Mark. “They’ll hold excessive rainfall and slowly weep it out.”

Altogether, Mark is pleased with the presence of his furry rodent forest co-residents. “They do a lot of the maintenance work. And at relatively low cost, in terms of what they eat. They’ve been a lot of fun.”

Resources on co-habitating with beavers

Frequently Asked Questions about Beavers – Washington Department of Natural Resources

Living with Wildlife: American Beaver – Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife

Species Factsheet: Beaver – Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife

Beaver, Muskrat and Nutria on Small Woodlands – Woodland Fish & Wildlife Series

Identifying and Managing Mountain Beaver Damage to Forest Resources – WSU Extension Forestry

Beavers Northwest – An awesome group that advocates for the many benefits beavers provide through research, outreach and landowner assistance.

Leave a Reply