Ecological Forestry Put to the Test for Birds

Deep in a forest on Washington’s Kitsap Peninsula, an orange-vested technician hikes through a dense, 40-year old conifer-dominated forest. He stops at a young cedar with low-hanging branches and pulls a sturdy plastic pouch out of his backpack. Inside is a small green circuit board shaped like a sticky-note. “AudioMoth” is written in white on one edge of the device.

The technician pulls a zip tie out of a pocket and uses it to attach the pouch to a low branch. A green light flashes on the device. Nodding at his work, he turns around and hikes on.

A top secret surveillance plot targeting Kitsap residents? Nope – just conservation science in action. These monitoring devices are indeed capturing audio, but only targeting the forest’s winged residents. They’re part of Great Peninsula Conservancy’s acoustic monitoring study of bird responses to specific conservation practices.

This forest, called Grover’s Creek Preserve, is one of several Kitsap Peninsula properties owned and stewarded by Great Peninsula Conservancy (GPC), a nonprofit land trust and a member of NNRG’s group FSC®-certificate. The lands and waters under GPC’s care are protected – forever. Through property purchases and conservation easements, the land trust is safeguarding more than 10,500 acres of ecologically important areas on the Kitsap Peninsula.

“The rapidity of residential and urban development in the Kitsap Peninsula makes it so important to set aside sites for the future,” says Adrian Wolf, GPC’s Stewardship Manager. NNRG has been working with GPC staff to develop management plans for many of their properties, including Grovers Creek Preserve, and gain Forest Stewardship Council® (FSC®) certification for nearly 500 acres of forestlands.

This bird monitoring study, funded by a $25,000 grant from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Land Trust Bird Conservation Initiative, is going to use recordings of birdsong and bird calls captured by the AudioMoth devices to understand how a set of ecological forest management activities impact bird populations. NNRG is one of the study partners, along with Daniel Froehlich (Ornithologistics), Dr. Alison Styring (The Evergreen State College) and graduate student Kayleigh Kueffner (The Evergreen State College).

Grovers Creek Preserve is one of five GPC properties that will be part of the acoustic monitoring study. Most of these forests were once industrial timberland, densely replanted with conifers after the last clearcut logging by the previous owner. Now they have little diversity in terms of species, stand structure, and tree age. “The interior of these even-aged and overstocked monocultures is essentially a biological desert: dark and lacking a diversity of understory shrubs and forbs. This habitat simplification directly influences the wildlife that could use these areas for cover, foraging, and breeding” laments Adrian.

Forest management as a tool for conservation

Ecological forestry practices like thinning, creating coarse woody debris, and planting a diverse mix of shrubs and trees, will help these forests develop more heterogeneously and become more resilient to climate change, which in turn will improve and sustain habitat for wildlife. Improving bird habitat is especially critical given the sharp decline in North American bird populations. In fact, GPC and its ornithologist partners identified 54 bird species that could benefit from the project’s forest management practices. “Ten are listed as ‘Species of Greatest Conservation Need’, eight are ‘Species of Continental Concern’, and four are ‘Common Birds in Steep Decline,’” writes GPC on their blog.

The project will be measuring bird response to three forest management practices.

Creation of snags, den trees, and coarse woody debris

In 2021 and 2022, GPC stewards girdled 424 trees across six sites. Girdling a tree severs the bark, cambium, the sapwood layer in a ring extending entirely around the trunk of the tree, which eventually kills the tree as it remains standing. Standing dead trees provide valuable shelter – and a food source – for dozens of bird species on the Kitsap Peninsula. In addition, GPC built 58 habitat piles and 27 constructed logs, which provide shelter for smaller, ground-dwelling birds and attract insects other birds feed on.

A technician cuts the bark and the cambium layer of a tree to kill it and create a standing snag. Photo courtesy of Great Peninsula Conservancy.

Creating structural diversity with patch openings

GPC will be making small patch cuts of 1.5- to 3-acres, often dropping cut trees on the ground to add large woody debris to the forest. These gaps mimic the natural disturbance a forest may face as a result of wind, fire, pests, or disease. The increased sunlight in cut area promotes the growth of early-seral shrub species that provide resources for an array of insects and foraging and breeding habitat for wildlife, including many bird species.

Replanting with a diversity of conifers and shrubs

In recently disturbed areas and in forests lacking in species diversity, GPC is replanting with a variety of native conifer, hardwoods, and shrubs. As they grow, these seedlings will convert these ruderal pastures and homogeneous, even-aged stand forests into a biodiverse haven for a greater variety of bird species.

The trees are alive with the sound of music

GPC is using AudioMoth acoustic devices to capture birdsong and bird calls in the forests where the three forest management techniques will be implemented. AudioMoths can capture sound at a range of frequencies, including sound emitted at frequencies too high for the human ear to hear (think, bat echolocation calls). Audio data is saved to an SD card in the device.

The AudioMoths will be deployed for two weeks before each forest management practice is implemented to establish baseline conditions. Then they’ll be deployed for two weeks after each practice has been completed to detect any changes in the bird community. GPC is focusing on 20 species that are most likely to respond to the forest practices. The AudioMoths are preprogrammed to capture three periods per day: once in the morning, once in the afternoon, and once in the evening. The two-week post-treatment recordings will happen two times per year: once in the spring and summer, and once over winter. At the end of each two week period, GPC staff retrieve the SD card from the AudioMoth devices and load the recordings into a software called Arbimon.

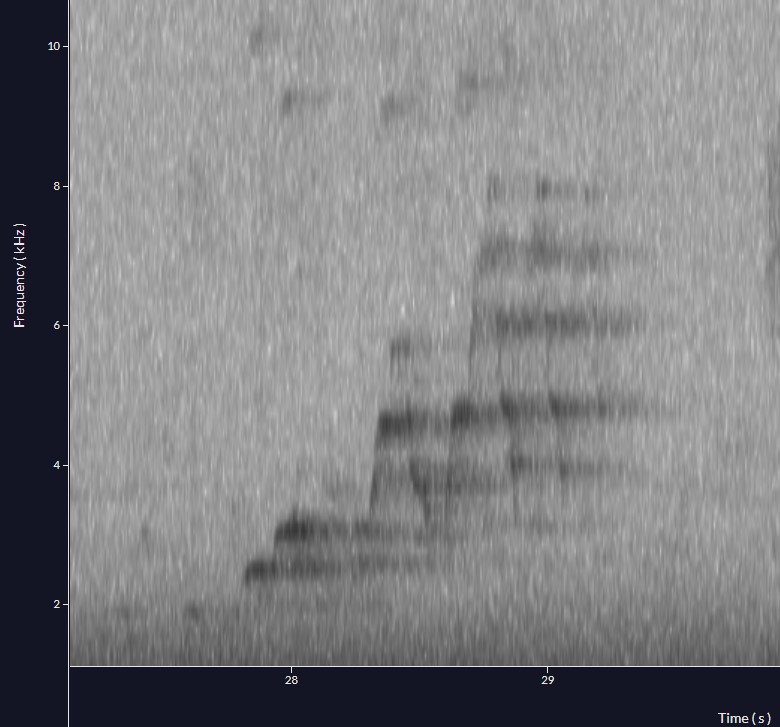

To the untrained ear, birdsong in a forest can sound like a blur of random vocalizations. But birds are making calls and singing songs in patterns unique to their species. The Arbimon software displays those patterns visually as sonograms. A Swainson’s thrush’s distinctive, ascending, ethereal song, for example, shows up like this:

Project partners and volunteers will listen to the recordings in Arbimon and, once species are initially identified, will “tag” the sonograms as belonging to those species. Once enough sonograms have been tagged as belonging to a particular species, Arbimon can then automatically search through other recordings for instances where those sonogram patterns show up – that is, for times when a very similar bird vocalization was recorded. “The software is cool,” says Adrian. “After a while, you can just visually inspect the sonogram and identify the species that is producing the song or call, without even hearing it. This software and state-of-the-art monitoring equipment offers tremendous opportunities for a better understanding of cryptic species, those that occupy remote places, and others that are active during times of the day when humans are generally asleep. Although I love to spend time in the forest at any hour of the day, I cannot be in more than one place at a time, and cannot pay someone to do that either. The remote monitoring devices allow researchers to collect thousands of hours of data from many locations at a time, and we can “teach” the software how to mine these data for our target species. The technology saves time and money, and ultimately, could help us understand how we could save species”.

Over time, Arbimon can be used to understand how the diversity and abundance of birds change in response to the three forest management practices implemented in GPC’s forests. The results of the project will be shared among project partners and with other land trusts and conservation organizations to inform stewardship efforts. While this project is slated to end June 2023, the AudioMoth devices can be redeployed at any point in the future to assess avian responses to the forest management practices over longer periods.

Listening to what the birds have to tell us

Efforts to expand and extend the acoustic monitoring study are already underway. GPC is applying for funding to do additional monitoring at its other properties, and is collaborating with the Jefferson Land Trust to initiate a similar project on their conservation lands. In addition to creating habitat features (down logs and standing snags) Jefferson Land Trust will be thinning about forty acres of dense, even-aged stands, and hopes to deploy the acoustic monitoring devices in those stands prior to, and after, the thinning.

Birds are excellent indicators of biodiversity and ecosystem health. A decline in bird populations or species diversity often indicates trouble in paradise. An increase can indicate an improvement in the overall health of the landscape. Keeping an eye – and an ear – on birds can tell us a lot about how we are and should be managing forests.

We are hopeful ecological benefits of the forestry practices implemented in this study will be corroborated by an improvement in bird species abundance and diversity on the Kitsap Peninsula. In the meantime, it can’t hurt to keep dead wood in the forest around. Chances are, it’ll make a great home for some wildlife this spring.

Leave a Reply