Getting to the Root (Rot) of the Forest

Phil Aponte has always loved forests.

When he was an interpretive ranger for Mount Rainier National Park, Phil had the chance to walk the woods with renowned forest ecologist Dr. Jerry Franklin. Jerry took a group of park rangers into a stand of old-growth forest and had the rangers lie down to observe their surroundings. As Jerry spoke, Phil recalls spotting a flying squirrel in the trees and feeling a great sense of peace. In that moment he knew he would steward a forest someday.

Phil and his wife Angela wanted a place they could call home, with a view of trees as far as the eye could see. Returning to town after a cross-country ski trip they noticed a sign advertising forested lots for sale. Soon after, they purchased a 20-acre tract in the McKenna Forest Reserve and made plans to live in a forest of their own.

The Apontes began moving onto their land in 2003. They built a home and garden. Raised their family. They enjoyed living among the trees.

Before they bought it, their land had been part of an industrial tree farm. They wanted to help this maturing tract of timber grow back into a structurally complex older forest that would support the full complement of native wildlife and plant species while supplying their family with wood for home use and periodic income.

About a decade after they acquired the forest, the Apontes brought in Northwest Natural Resource Group (NNRG) to update their forest management plan. Kirk Hanson, NNRG’s Director of Forestry, inventoried the stand and located several areas where the Douglas-fir were falling prey to root rot. What’s more, the understory was so shady that the shrubs and seedlings on the forest floor were struggling to find enough light to survive.

In the root rot areas, the 40-something-year-old Douglas-fir trees showed signs of decline and were blowing down during wind storms. Root rot is a normal part of a healthy forest and an important agent for creating gaps and conditions that increase biodiversity. The small clearings around a fallen tree create patchiness in the canopy—what forest ecologists call “spatial diversity”. Native trees and understory plants soon fill in this unoccupied space.

The root rot pockets in the 20-acre forest had developed several nice gaps. Rather than let the root rot spread further or infected trees knock down healthy trees, the Apontes decided to do a commercial thinning with the goal of reducing the root rot.

The Apontes’ forestland had previously been owned by an industrial timber company, which managed the land to maximize economic returns. Its workers had planted the tract with Douglas-fir, at 450 trees per acre, or about 10 feet between trees. Around 1998, the forest had been thinned to 140 trees per acre. This treatment set up the remaining trees to grow into high-quality peeler grade logs — logs that could be peeled for veneer that is used to make plywood.

Planning the Harvest

The Apontes worked with NNRG to plan the timber harvest. NNRG prepared the Forest Practice Application, marked the trees for removal, flagged buffers around the property lines, helped the family select the logging operator, and marketed the trees to local mills to obtain the best value possible.

They hired logging operator Boehme and Sons to complete the thinning work.

It took about three weeks for JD Boehme and three other members of his crew to carefully thin the Apontes’ 20 acres. The thinning took the stand from 140 trees per acre down to 90 trees per acre. The harvest generated two kinds of logs: peeler (or export) grade, which comprised 91 percent of the material, and lower-quality logs to be pulped.

After harvest, the stand’s diversity is evident: western redcedar, western hemlock, bigleaf maple, red alder, Oregon ash, bitter cherry, are all part of the forest.

The understory trees and shrubs have additional light and space to grow, including sword ferns, salal, hazel, and oceanspray. Snags and down logs are available for wildlife, and windthrow of trees on the edge of the property is creating some additional down wood.

Harvest Stats & Revenue

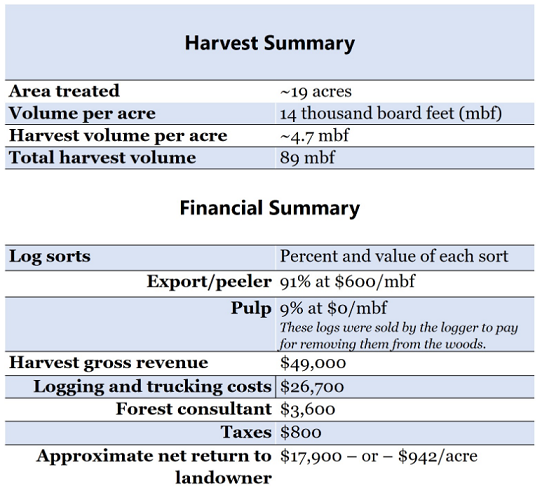

Below is a financial summary from the thinning project on the Aponte family’s forest. This was the second thinning for the 42-year old stand. The first commercial thinning — carried out by the previous owner in 1998— set up the stand to grow high-quality timber.

The primary objective of this thinning was to reduce the spread of root rot, create opportunities to further diversify the forest, and set the stand up for another selective harvest in approximately 20 years. Revenue from the timber harvest provided the family with a respectable return.

The Future of the Forest

It’s now been six years since the thinning, and Phil hasn’t seen root rot return to the harvested areas. It’ll be a while before he plants Douglas-fir in those areas again, as the fungus can live on in small roots in the soil for 10 years or more after host trees are removed. In the meantime he’s been planting 100 to 150 trees each year to add variety to the forest, including western redcedar, grand fir, noble fir, and some western larch – a favorite tree. He’s also stayed on top of manually removing the abundant tansy ragweed, foxglove, holly, vetch, and scots broom starts.

Understory vegetation in the forest is slowly becoming more complex. Phil’s seen a lot more bigleaf maple coming back since the harvest, as well as some vine maple, various types of ocean spray, Indian plum, and some alder.

When Phil is outside taking care of the forest he’s also able to observe more wildlife. Lately he hears barred owls and has seen a family of great horned owls on a regular basis, noting they are likely competing for territory.

The long evenings of late spring through early fall are prime time to get out in the woods after work. It’s also when Phil watches the robust population of little brown bats that live in his woods and fly about, sometimes roosting in one of Phil’s bat boxes.

The land is well on its way to becoming a healthy, thriving forest, thanks to the thinning work several years ago and the Apontes’ continued stewardship.

This story was originally published as an ArcGIS storymap in 2017.

For forest owners interested in developing management plans or accessing cost-share to fund conservation practices consider these resources:

Developing a Forest Management Plan

Environmental Quality Incentives Program

For more examples of landowners practicing ecological forestry, check out these stories.

NNRG wishes to thank Western Sustainable Agriculture and Education for the support to curate this story and develop tools for forest owners.

Leave a Reply