About the Hansons

My family began its forestry tradition in Minnesota before I was born when my parents acquired a tract of forestland in the early 1960’s in the St. Croix River Valley.

The forest across this parcel was largely comprised of second growth hardwoods – sugar maple, red and white oak, birch. White pine was once the dominant old growth species across the upper Midwest before Weyerhaeuser, a small logging company that began in Wisconsin, and other logging companies, gradually gnawed their way west until they hit the unlimited old growth of the Pacific Northwest.

My parents spent countless days planting white pine in the understory of the 2nd generation hardwoods, protecting the seedlings from deer browse, and eventually thinning the oaks and maples to make way for the return of the pine as it gradually eclipsed the forest canopy. We tapped the sugar maples in the spring, and boiled the sap down to maple syrup. We cut endless cords of firewood from the diseased red oak as it slowly expired to a root fungus that was epidemic throughout the forest. We filled water jugs from natural springs that seeped from the porous sandy soils. And we recreated: hiking, camping, cross-country skiing, snow shoeing, and simply pondering the mystery of the firmament.

When I moved west over 25 years ago it was practically an existential imperative that I acquire my own forestland into which I could send down roots, make sense of this world, and pursue the endless fascination of tinkering in the woods. In 1995 my sweetie and I purchased our first tract of land, what I now refer to as our homestead property, South of Oakville, WA in the northern extent of the Doty Hills, which comprise the northern terminus of the Willapa Range that in turn stretches southwest towards the coastline. The Willapa Range is a massive series of ancient marine deposits. If one scrambles down the deeply incised seasonal stream drainages on the north side of the hills, one will find a horizon of sedimentary soil choked with seashells; evidence of the era when these antediluvian marine terraces were submerged beneath saltwater. Over eons of subduction, the Pacific Plate ground its way beneath the Coastal Plate, shoving the current shoreline up out of the ocean, exposing the marine terraces and setting into motion the processes of ecological succession that has led to the most massive stands of timber our planet has ever known, second only to the redwood forests of northern California.

The old growth is long gone. My homestead property now supports a third generation forest comprised largely of young Douglas-fir and red alder. Ghosts of the former old growth still linger in the shadows of my woods in the form of large stumps and downed logs – but these have nearly faded to nothingness, and require a keen eye to find. This parcel was mostly clearcut by the previous owner and replanted entirely to Douglas-fir. At the time I had little time and less money to invest in managing the new fir plantation, so through a default silvicultural policy of benign neglect I allowed naturally regenerating red alder to colonize the lower slopes and wetter sites of the land, outcompeting the fir in these areas, but lending what I came to learn was another very valuable timber species. In the intervening years many other tree species found their way into the young plantation – bitter cherry, maple, cascara, others – and I watched with fascination as Mother Nature took a homogeneous plantation and quickly wove in an extraordinary array of diversity.

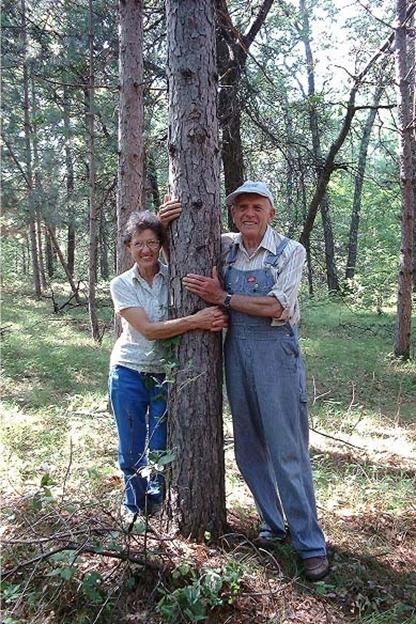

About 10 years ago my parents decided to move west to be closer to my family, and with a fond farewell sold the original family forest in MN.

I helped them to immediately purchase a comparable amount of forestland near Black Diamond, WA taking advantage of a tax break on capital gains afforded to those who reinvest real estate earnings in similar real estate. They acquired the property from Weyerhaeuser, the tract having been part of the original 900,000 acres that Frederick Weyerhaeuser purchased from the Northern Pacific Railway in 1900 when the company decided to begin lumber operations in WA. Having liquidated most of its original old growth assets in less than 50 years, the company pioneered the concept of sustained yield harvesting by establishing monoculture plantations of Douglas-fir which were intensively managed for timber production.

The parcel my family acquired fit this model perfectly, as it was stocked with a solid mass of Douglas-fir packed in at nearly its original planting density of 350 trees per acre, or a tree every 12 feet. Competition mortality and disease had slightly reduced the stocking, and allowed for a smattering of alder and cottonwood to filter in, but otherwise this forest was about as classic of a tree farm as you will find.

My family recently bought a new tract of forestland near Bucoda, WA about five miles north of the town of Centralia. The land straddles a clay hill that is part of the same vast ripples of prehistoric marine sediment laid down millions of years ago that underlie our Oakville forest. This forest presents a new adventure for us – stands of young planted Douglas-fir, patches of naturally regenerated red alder, acres of brush that are an artifact of past poor management. We did what all good farmers do – we bought good soil, but the land needs active stewardship if it’s going to yield dividends to those who steward it…