Longer Rotations and Carbon

It’s no secret that contemporary industrial timber practices fall short of realizing the potential of Pacific Northwest forests to sequester carbon. Whether it’s the allure of quick financial returns, the constraints of high discount rates, or the notion of fiduciary responsibility, most industrial owners west of the Cascades cut their evergreen forests soon after they grow to merchantable size — at 35 to 45 years old, depending on the growing conditions on the site.

And yet, that practice ends the trees’ career as photosynthesizers and timber manufacturers just when they’re getting good at it. Douglas-fir, for example, hits its stride in this region at age 25 or 30, and doesn’t slow down much until well past 70 years old, depending on the site.

So I began to wonder just how much more carbon could be sequestered — and timber produced — if forest owners shifted to a longer rotation. To answer this question, NNRG forester Jaal Mann used the US Forest Service’s FVS model to run a thought experiment on two hypothetical acres of forest near Chehalis, Washington. Imagine that the trees were planted in 1980, had been pre-commercially thinned at age 10, and commercially thinned at age 30.

Now it’s 2020, the trees are 40 years old, and two paths diverge in these woods: one acre is clearcut and replanted, while the other is put on a track to an 80-year rotation. It will be thinned at age 45, thinned again at 60, and then clearcut at age 80. At that point, it will be replanted and start that same 80-year cycle again

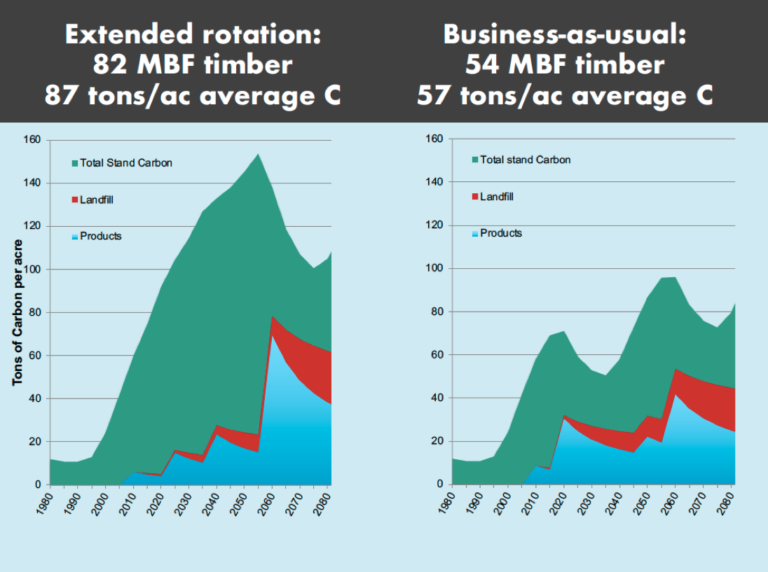

Besides tracking timber production, we used FVS to follow the fate of carbon that had been stored in the forest. We looked at three places carbon could reside that would keep it from returning to the atmosphere and making mischief with the climate: in the products made from harvested timber, in the landfill after those products had completed their useful lives, and total carbon stored in the forest itself.

The following graphs show what we found: doubling the rotation age increases timber production by 52 percent over the 80-year planning horizon. What’s more, over 100 years — the standard time frame to measure carbon sequestration — the longer rotation keeps 53 percent more carbon, on average, out of the atmosphere.

Biophysically, it’s no surprise why this would be the case. When you clearcut the forest, you destroy the forest’s photosynthetic infrastructure that converts light, water and CO2 into wood and oxygen, and it takes a while to rebuild it. For 10 to 15 years, most of the photons falling on that acre are wasted for purposes of driving long-term carbon sequestration: they fall between the seedlings, or on trees that will be pre-commercially thinned and then promptly decay. Clearcutting twice as frequently means that the forest spends more time in that less efficient rebuilding phase.

In a way, rotation age is like a Marshmallow Test for forest owners: an experiment in delayed gratification. In the test, an experimenter puts a marshmallow in front of a preschooler and tells them if they hold themselves back from eating it for 15 minutes, they can have a second one as well as the first. Although correlations between the Marshmallow Test and life outcomes have been debunked, it remains a metaphor for short- and long-term thinking.

Would you be able to resist? Click here to watch the marshmallow test in action.

For forest managers who take a multi-purposed approach to their forest, this is just one more argument for raising older forests — which also produce benefits for wildlife, water yield, and salmon habitat. If you can be patient, the forest will reward you.

But what about forest owners whose primary motivation lies in the short-term bottom line? Over the last century, our body politic has periodically described new societal benefits that it expects forest owners to produce: sustained production of timber, clean water, salmon habitat. If society now wants to add enhanced carbon storage to that list and enlist financially driven forest owners in that cause, it may have to speak to them in Benjamins — either with payments for carbon storage, or a ‘feebate’ structure to the Forest Excise Tax that charges extra for cutting on a short rotation, and uses that money to lower the tax burden on harvests that leave the forest stocked with growing timber.

Either way, it will take a change to the rules of the road for Pacific Northwest forest stewards to fully realize their land’s prodigious potential to store carbon. But it’s heartening to know that the carbon bank is there and ready to accept deposits if and when we choose to fully use it.

Leave a Reply