Soil Stewardship Basics

Forest stewardship can be thought of as synonymous with soil stewardship. Healthy soils sustain wildlife habitat, grow high-quality timber, improve your forest’s resilience to stressors like drought, heat, and pests, and store carbon.

So how does one become an expert in forest soils? Below we outline the fundamentals of soil stewardship and direct you to further reading on the subject.

1. Understand the soil types in your area

Understanding the soil types in your forest will help you make informed forest management decisions about road building, harvesting, site preparation, planting, thinning, and more. Knowing the physical properties of your soils—such as texture, porosity, density, water capacity, drainage class, depth to bedrock or root-restricting layers, temperature, and erodibility—can help you determine road placement, harvest areas, harvest systems, what species to plant, and what areas might be prone to windthrow.

Jeanie Taylor—a plant propagator, garden coach, horticultural instructor, and steward of Taylor-Lennon Family Forest in Oregon—recommends everyone first look up the soil series in their area using the Natural Resource Conservation Service Web Soil Survey. The tool provides soil data and information produced by the National Cooperative Soil Survey. It allows you to select an area of interest, then view and print a soil map and detailed descriptions of the soils in that area.

2. Do a soil survey in your forest

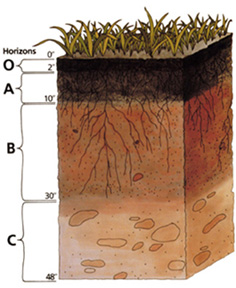

To examine your soils firsthand you can dig a soil pit. Digging a soil pit will allow you to view the soil horizons and confirm the soil type in a specific area. WSU Extension Forestry recommends digging a soil pit somewhere that isn’t too steep, isn’t too level, and is representative of the surrounding forest. And, avoid digging a pit right next to a tree or where there’s been recent heavy equipment or building activities, as these will all make the digging more difficult. The dimensions of the pit will depend partially on your energy (digging is tiring!) but most recommend digging around 2-3 feet deep. In many soils, this will make most of the soil horizons visible. The arrangement of the soils horizons (layers of soils) is called a soil profile.

According to the Natural Resource Conservation Service, “Most soils have three major horizons — the surface horizon (A), the subsoil (B), and the substratum (C). Some soils have an organic horizon (O) on the surface, but this horizon can also be buried. The horizon E, is used for subsurface horizons that have a significant loss of minerals (eluviation). Hard bedrock, which is not soil, uses the letter R.”

Each soil horizon has a unique combination of physical properties, each of which tells you something about the soil.

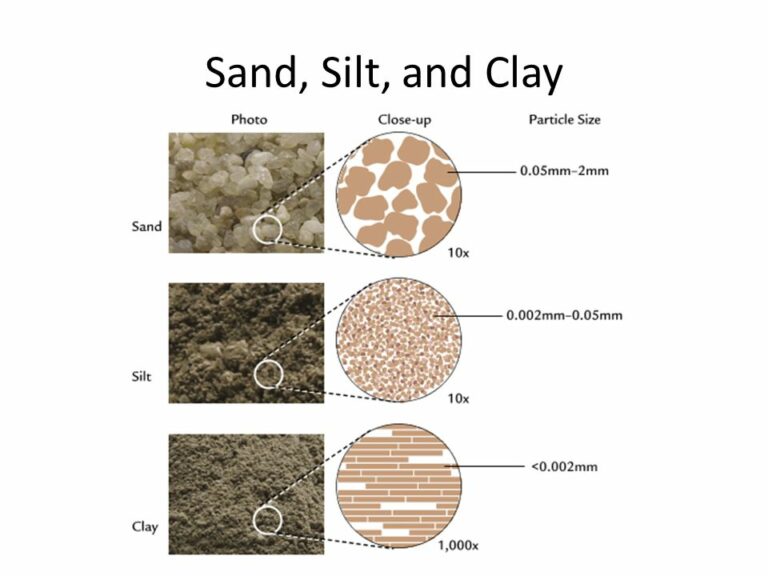

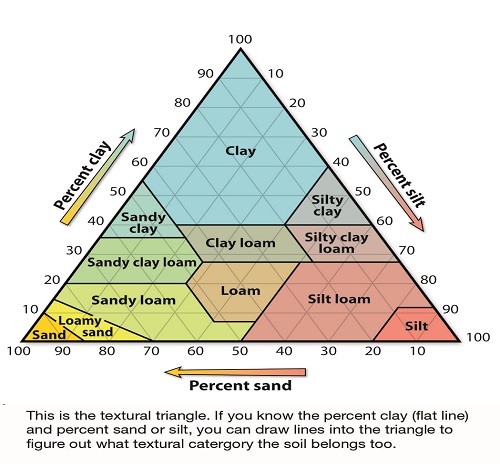

The texture of a horizon indicates the proportion of particles in the soil that are originally derived from rock. Texture is influenced by particle size and pore space (the empty space between particles). Most soils are comprised of varying ratios of sand, silt, and clay. Sand particles are the largest, and therefore have the largest pore spaces. Clay has very fine particles and the least pore space between them. Silt is somewhere between the two in terms of particle size and pore space. Particle size and pore space influence the soil’s ability to store nutrients and hold and drain water. The larger the pore space, the faster water will drain.

Soil scientists classify soil into groups according to the relative percentage of sand, silt, and clay particles. A soil “mudshake” test can help you determine roughly what group your soil is in. Another version of the same test can be found here.

Understanding soil structure is as important as understanding the texture of your soil. Two soils with the same texture can behave very differently depending on their structure. For example, clay soil can be easy for air, water, and roots to move through if it has “good” structure, but it can be almost impenetrable by roots, air, and water when its structure has been destroyed by compaction. Soil structure also heavily influences carbon-storage capacity. Soil with good structure has stable pore spaces that allow water drainage, root growth, earthworm movement, and air storage.

To learn more about soil texture and structure, check out Jeanie Taylor’s recent presentation on matching soils and native plants.

3. Limit soil compaction

The management practices you employ in your woods can protect high quality soils and improve degraded soils.

“Probably the most important thing to remember,” says Jeanie Taylor, “is to avoid compaction, preserve the structure, and know how to do that by entering the site with equipment at the appropriate time.” When soil is compacted, pore space decreases and reduces space for gas exchange, nutrient filtration, and water drainage. In general, try to avoid conducting harvest activity when soils are wet. Thinning slash can be scattered across skid trails during harvests to minimize compaction from heavy equipment, return nutrients to the soil, and protect soil from erosion. Learn more about managing soil compaction and limiting soil disturbance in Chapter 5 of Best Management Practices for Maintaining Soil Productivity in the Douglas-fir Region, an OSU Extension publication.

4. Monitor your soils over time

Monitoring your soils throughout the year and over time is important for understanding how management activities and external environmental changes are affecting them. Record what you find during your first soil survey and soil texture tests, and conduct additional soil surveys and tests over time. A forester can help you investigate what changes in soil composition, texture, or levels might mean for your forest.

Soil Resources

NRCS Web Soil Survey – An online tool that allows you to view and download maps of soil surveys in your region.

Forest Soil data for Your Forest Stewardship Plan (PDF) – This manual is a step-by-step guide through the process of getting soil information from the USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service’s (NRCS) Web Soil Survey (WSS).

Keeping Your Forest Soils Healthy and Productive – This publication by WSU Extension includes background on the fundamentals of good forest soil stewardship.

Digging a soil pit on your property – WSU Extension YouTube video explaining how to dig a soil pit in your forest.

Best Management Practices for Maintaining Soil Productivity in the Douglas-fir Region (PDF) – This publication by OSU Extension has in-depth recommendations for maintaining soil health in Douglas-fir forests.

Managing Organic Debris for Forest Health (PDF) – This publication outlines the role of forest organic debris in Inland Northwest forests and provides general management recommendations to maintain forest soil productivity and improve wildlife habitat.

Leave a Reply