NNRG Intern Highlight: Assessing the Impacts of Down Wood in Puget Sound Douglas fir EcosystemsLiving Dead Forests

Article by Forrest Becker – This research was conducted as part of the requirements for a Master of Arts in Climate Change and Global Sustainability at SIT Graduate Institute, USA.

The grounded logs and branches from fallen trees play a crucial role in the Pacific Northwest’s forest ecosystems. Sometimes mistaken for a negative waste product, ‘down wood’ represents the end of a tree’s life cycle but can also enable future life by providing habitat and nutrients to diverse wildlife and plant communities. This is exemplified in ‘nurse logs,’ a phenomenon where fallen trees create a foundation for seedlings, providing nutrients to future tree generations while creating remarkable landscapes for hikers to traverse.

These beneficial processes are known as ecosystem services. We benefit from down wood but can as easily suffer from it when dry wood fuels wildfires, releasing climate-changing carbon into the air. To see down wood in action, look no further than the Olympic Peninsula’s plentiful nurse logs!

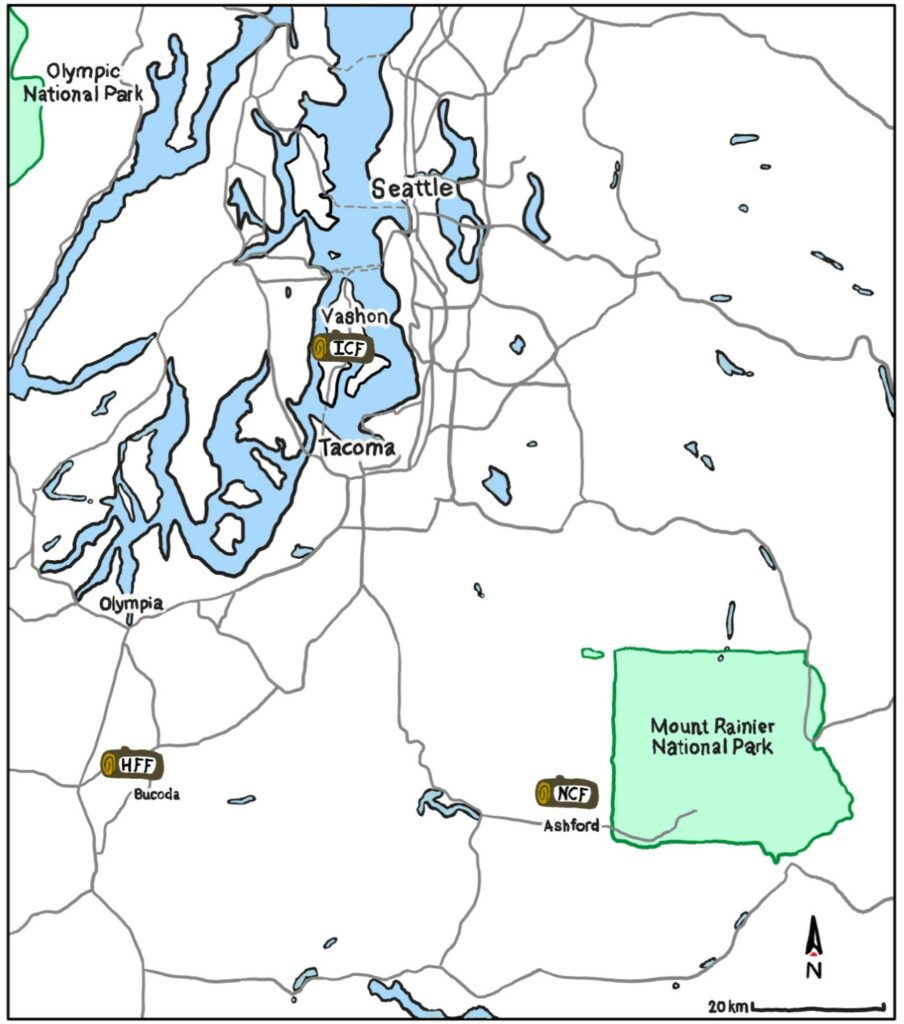

Inspired by Northwest Natural Resource Group’s ecological forestry model, I set out to study down wood in the Puget Sound region’s Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) forests. There was just enough scientific literature to inform my study methods, but few studies estimate how much carbon, water, wildlife, or other value the down wood contains here in Western Washington. I surveyed and sampled thirty different logs in Nisqually Community Forest (NCF), Island Center Forest (ICF), and H. F. Forest (HFF) to find out what down wood does for us. The NCF plot is unique for its higher elevation and fish-bearing stream, around which a ‘buffer zone’ protects stream ecology from ordinary management activities. The ICF plot sees the most intense human use, the ecologically thinned forest accessible by a network of trails. The HFF plot is in a private forest supporting the greatest tree species diversity of any sampling sites.

Using an “increment borer” to drill into the logs, I extracted samples from bark to core along the length of each log. I also measured each log’s dimensions, surveying wildlife and landscape characteristics to better illustrate these systems.

Across all three sites, I collected 150 samples and dehydrated them to differentiate between wood and water weights. The dry wood weight is 50.6% carbon in the kind of wood I sampled for this project. With those components measured, I was able to statistically analyze my findings.

I recorded significantly more species of fungi, plants, and animals in NCF than in the public and private forests studied, though the private forest, HFF, had significantly more species of down wood than the community forest did. Wood volume and biomass at NCF was consistent with undisturbed, mature forests, though ICF and HFF were far lower. Biomass, carbon and water contents were not significantly different between management scenarios, but the more decomposition the less biomass and carbon. Carbon content in each forest was considerably lower than the carbon stored in a nearby old-growth forest, while water content was markedly higher. There was a relation between log volume and the number of species living on it, though the trend became weaker when including particularly large “outlier” logs. Higher carbon content generally promoted higher water content, though not in advanced stages of decay or in the private forest, ICF.

I also had the pleasure of interviewing two of the forest managers and two forest stakeholders to understand how residents and experts perceived the benefits and drawbacks of keeping dead trees around. Managers tended to emphasize wildlife, decomposition, and wildfire dynamics within down wood. Stakeholders, including one landowner and one recreationist, were more fond of the aesthetics of down wood alongside wildlife habitats.

These findings suggest that down wood’s ecosystem services vary across management and climate contexts, and in the minds of the people who interact with it. The Puget Sound region’s down wood stores a lot of water but very little carbon, decreasing the risk of wildfire fueling under severe climate change. Management which promotes the recruitment of large down wood to the forest floor will better benefit humans and ecosystems by attracting wildlife, cycling nutrients, enabling soil formation, and enchanting hikers. How humans choose to value down wood will have a large impact on whether its services are available far into the future. These findings help to build our scientific understanding of down wood and the ways it enables the beautiful, diverse, and often complicated environments we live among in the Puget Sound region.

Leave a Reply