Out With the Fir, In With the Oak

Sarah Deumling has noticed some changes in her forest over the past 20 years.

There’s a little less water to go around, and her family’s land, Zena Forest in the Willamette Valley of Oregon, is a little hotter and drier during the summer. Why? These changes are consistent with climate models’ predictions of the way Oregon climate is shifting under the influence of global warming.

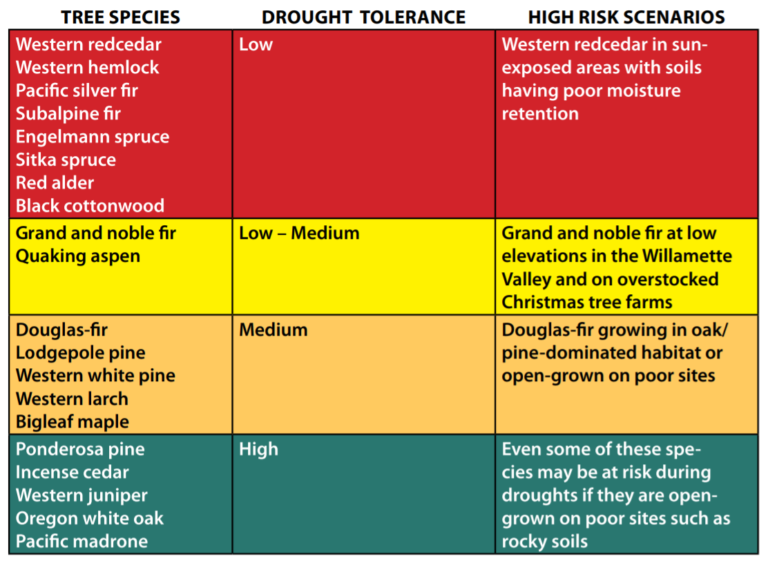

Douglas fir appears to have been the hardest hit by the changes in summer water flows and temperature. In the Willamette Valley, Douglas fir is a comparative newcomer, and seems least adapted to projected changes in climate patterns. The oaks, on the other hand, are doing relatively well. Her conclusion is that oaks are a winner for a lot of drought tolerance and heat reasons.

Historically, oak and maple have been more dominant in the area. Frequent low-intensity fires, often purposefully set by indigenous peoples, favored open landscapes dotted with hardwoods like oak and maple. The burn suppression that the Northwest has experienced in the last 150 years has selected for conifers instead.

Tree species that have adapted to the current climate in areas like the Willamette Valley may struggle when exposed to different climates long-term.

Douglas fir will probably diminish over time as a percentage of the species, especially at lower elevations with southwest exposure on poor soil.

Meanwhile, native oak may prove hardier under a changing climate. Their deep roots and diverse fungal associations help them adjust to dry, hot environments.

Projections predict that at the end of the century, local climates will look very different to how they look now.

A University of Maryland model shows that in a high-emissions scenario, the climate around current-day Salem will be similar to the current climate of Sacramento.(You can check the potential impact to your area using this link: https://fitzlab.shinyapps.io/cityapp/)

Knowing what the future might hold, Sarah has been taking proactive action for the last 15 years by sourcing Douglas fir seedlings from farther south, where they may already be adapted to a warmer and drier climate.

Her family has also been leaving slash on the ground to help retain soil moisture.

Sarah looks to the understory when deciding planting. Ferns indicate a wetter area that will help support Maple and Fir, while poison oak, snowberry, and honeysuckle indicate a drier area that can support other hardwood species. Looking to the understory shows which species will thrive based on exposure and moisture.

Irrigation in drier areas is out of the question, so they’ve been on a hunt to find trees that will survive. Her family has also been replanting with more drought tolerant species, particularly sequoia, incense cedar, pine, and oak. Sequoia isn’t currently grown as a timber species in Oregon so there isn’t much of a market for it. But recent research indicates that middle-aged sequoia may well be a marketable wood in the future. The Deumlings hope that these trees may turn out to be an economic as well as an ecological asset.

Sarah urges others not to overlook the ecological and economic benefits of hardwoods. In addition to their merchantable value, hardwoods tend to be more fire resistant than conifers due to their lower oil content and they are very important to birds, insects and other critters.

“In the Willamette Valley, the land simply doesn’t want to grow conifers at the same rate as other areas in the northwest,” Sarah noted. “Landowners need to manage oak and other hardwoods as an asset, rather than a liability.”

When in doubt, you can hedge your bets and grow both.

Leave a Reply