The Ever-Evolving Hanson Family Forest

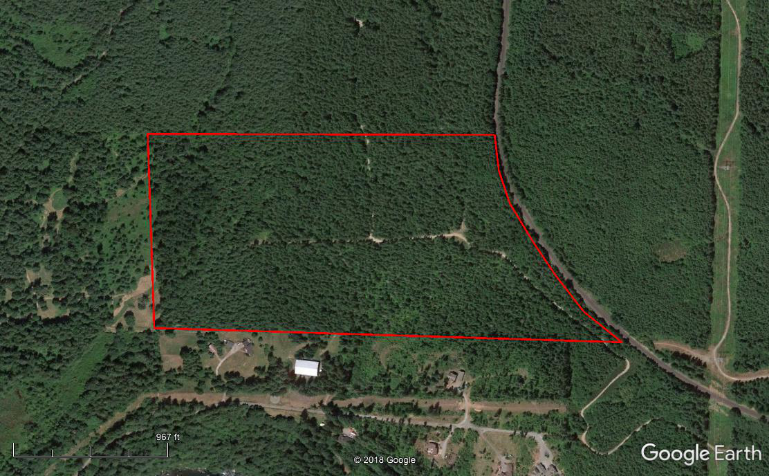

My family recently bought a new tract of forestland near Bucoda, WA about five miles north of the town of Centralia. The land straddles a clay hill that is part of a vast ripple of prehistoric marine sediment laid down millions of years ago when this area was submerged beneath the Pacific Ocean. The soils, a residuum of weathered sandstone, glacial rock, and volcanic ash are incredibly fertile when unlocked with a biologically active humus. Combined with abundant rainfall and a mild maritime climate, this region of Southwest WA is home to one of the most productive forest ecosystems in the world.

The forest that currently covers my family’s new land is an artifact of decades of timber harvesting and is comprised of a mish mash of different ages and species of trees. Some of the stands are already in their fourth generation of growth, which speaks to the productive and regenerative qualities of forests in our region. The majority of the southern portion of the property is comprised of a young 27-year old Douglas-fir plantation. Homogeneous in species and age and with such a dense canopy that little to no understory vegetation survives beneath the skirts of the branches, this stand is nearing the age of its first commercial thinning.

The northern portion of the property is the most heterogeneous and interesting. Over the past 20 years the prior generation of forest was harvested in small patches, some harvest units replanted, and some not. Consequently, the area is comprised a wide mix of stand types, including:

- Naturally regenerated thickets of red alder intermixed with bitter cherry, cascara and young big leaf maple;

- Recently planted cedar, Douglas-fir and alder that are struggling against a surging green tide of non-native and invasive blackberry and sprouting stumps of maple; and

- Many acres dominated by a nearly impenetrable jungle of brush – vine maple, hazel, cascara – punctuated by periodic alder and big leaf maple.

This forest comes as an addition to two other tracts of forestland my family has acquired over the years in Washington, and furthers a family tradition of forest stewardship that spans more than 60 years and three generations.

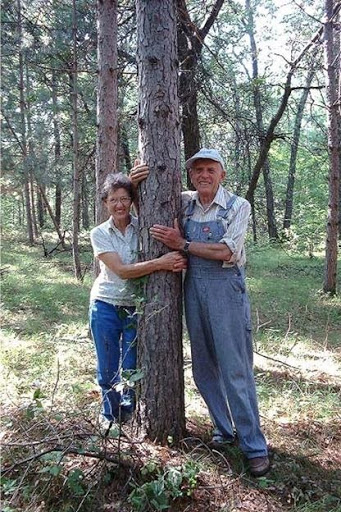

My family began its forestry tradition in Minnesota before I was born when my parents acquired a tract of forestland in the early 1960’s in the St. Croix River Valley. The forest across this parcel was largely comprised of second growth hardwoods – sugar maple, red and white oak, birch. White pine was once the dominant old growth species across the upper Midwest before Weyerhaeuser, a small logging company that began in Wisconsin, and other logging companies, gradually gnawed their way west until they hit the unlimited old growth of the Pacific Northwest.

My parents spent countless days planting white pine in the understory of the 2nd generation hardwoods, protecting the seedlings from deer browse, and eventually thinning the oaks and maples to make way for the return of the pine as it gradually eclipsed the forest canopy. We tapped the sugar maples in the spring, and boiled the sap down to maple syrup. We cut endless cords of firewood from the diseased red oak as it slowly expired to a root fungus that was epidemic throughout the forest. We filled water jugs from natural springs that seeped from the porous sandy soils. And we recreated: hiking, camping, cross-country skiing, snow shoeing, and simply pondering the mystery of the firmament.

When I moved west over 25 years ago it was practically an existential imperative that I acquire my own forestland into which I could send down roots, make sense of this world, and pursue the endless fascination of tinkering in the woods. In 1995 my sweetie and I purchased our first tract of land, what I now refer to as our homestead property, just South of Oakville, WA. Something that is unheard of today, I had just enough college tuition money left over after graduating to make the down payment on the land. Life a forced savings plan, we put every spare penny we earned into paying off the land in 10 years. This forest exists in the northern extent of the Doty Hills, which comprise the northern terminus of the Willapa Range that in turn stretches southwest towards the coastline. The Willapa Range is another massive series of ancient submarine clay ripples comprised largely of the same soils that underlie our newly acquired Bucoda forest. If one scrambles down the deeply incised seasonal stream drainages on the north side of the hills, you will find a horizon of sedimentary soil choked with seashells; evidence of the era when these antediluvian marine terraces were submerged beneath saltwater. Over eons of subduction, the Pacific Plate ground its way beneath the Coastal Plate, shoving the current shoreline up out of the ocean, exposing the marine terraces and setting into motion the processes of ecological succession that led to some of the most massive stands of timber our planet has ever known, second only to the redwood forests of northern California.

The old growth is long gone. My homestead property now supports a third generation forest comprised largely of young Douglas-fir and red alder. Ghosts of the former old growth still linger in the shadows of my woods in the form of massive stumps and downed logs, but these have nearly faded to nothingness, and require a keen eye to find.

This parcel was mostly clearcut by the previous owner and replanted entirely to Douglas-fir. At the time I had little time and less money to invest in managing the new fir plantation, so through a default silvicultural policy of benign neglect I allowed red alder to colonize the lower slopes and wetter sites of the land, outcompeting the fir in these areas, but lending what I came to learn was another very valuable timber species. In the intervening years many other tree species found their way into the young plantation – bitter cherry, maple, cascara, others – and I watched with fascination as Mother Nature took a homogenous plantation and quickly wove in an extraordinary array of diversity.

About 10 years ago my parents decided to move west to be closer to my family, and with a fond farewell sold the original family forest in MN. I helped them to immediately purchase a comparable amount of forestland near Black Diamond, WA taking advantage of a tax break on capital gains afforded to those who reinvest real estate earnings in similar real estate. They acquired the property from Weyerhaeuser, the tract having been part of the original 900,000 acres that Frederick Weyerhaeuser purchased from the Northern Pacific Railway in 1900 when the company decided to begin lumber operations in WA. Having liquidated most of its original old growth assets in less than 50 years, the company pioneered the concept of sustained yield harvesting by establishing monoculture plantations of Douglas-fir and managing them intensively for timber production. The parcel my family acquired fits this model perfectly, as it is stocked with a solid mass of Douglas-fir packed in at nearly its original planting density of 350 trees per acre, or a tree every 12 feet. Competition mortality and disease have slightly reduced the stocking, and allowed for a smattering of alder and cottonwood to filter in, but otherwise this forest was about as classic of a tree farm as you will find.

The Douglas-fir on our Black Diamond tract was about 27 years old when we purchased the land, and just coming of age to be merchantable. Within a couple years of acquiring it, we commercially thinned the forest, recovering some of our investment, but more importantly reducing the stocking density to the point where the remaining trees, the dominant and higher quality ones, could continue to grow and gain in volume and value. The mechanical disturbance of the soils by the logging equipment also created an ideal seed bed into which other trees are now beginning to germinate – alder, hemlock, cedar and more Douglas-fir – lending diversity and sowing a future crop of timber.

I’ve found that getting to know each of these forests is like embarking on an entirely new intimate relationship. The excitement of the unknown and the process of discovery is thrilling. The idiosyncrasies are at first benign curiosities and reveal a more complex character that beckons to be known and understood. Though the novelty of being in a working relationship with any of our tracts of forestland has yet to wear off, they do require work, and sometimes a lot of work, and their ability to captivate my attention often supplants other life pursuits. Although I would not compare any of them to a fickle mistress, they can seem quite aloof, and I can’t help but wonder if left alone they wouldn’t be better off, as though I’m in a one-sided codependent relationship. I know I need the forest for my own grounding and sense of purpose, but I don’t think the forest necessarily shares that sentiment.

Back to our Bucoda tract (and yes, we are working to find better names for our forests). I’m not entirely sure what it is about this particular forest, but it has utterly captured my fascination – in some ways more than the previous two. It is more than simply being new, or a focal point for my lifetime of forestry experience, or a complex suite of challenges to solve, or the potential for coaxing it into robust productivity. Perhaps it is simply the undefinable esprit des lieux that draws a person in to the deepest of relationships – that between the individual and the universe.

Perhaps it is the little grouse that has greeted me at the entrance to this forest without fail the past half-dozen times I’ve been there. Perhaps it is the honey bee hive I discovered in a cavity in a large cedar who, despite the collapse of their civilization across the rest of our country, have sought refuge on my family’s land and will hopefully persist. Perhaps it is the lone birch I found struggling in the understory of a dense alder stand, far outside its normal territory, a solo traveler who staked a tenuous claim on our land, boldly defiant of the future in the absence of a mate.

Things like that speak to me, draw me in, and evoke such a deep experience of love and belonging that I can’t help but return, and can’t help but want to give back – even when the recipient is aloof.

One Comment

Really enjoying your book , ‘A Forest of your own’, that I picked up at clackamas tree school. I hope it is ok that I posted it on my instagram page that I have for my family forest! #theplaceatlacomb